Texas takes small steps toward medical cannabis

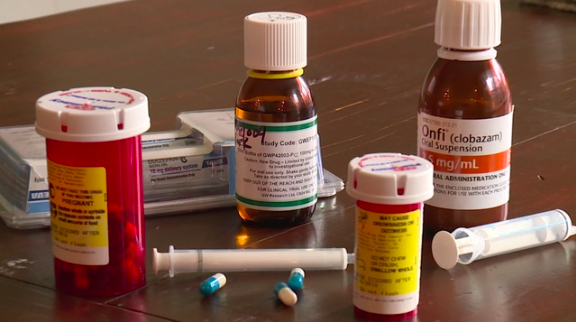

Texas is the last major state to allow some form of medical cannabis. The state’s limited program only allows for an oil extract that is very low in the psychoactive component THC.

The license fees to grow cannabis in Texas are the highest in the country, at nearly $500,000, and the state has licensed eight doctors to prescribe this low-dose oil. Like other states, access is limited to a small pool of patients who have been diagnosed with epilepsy and have tried at least two other treatments first.

Moreover, growers are required to have surveillance videos of every square foot of their facility and to preserve recordings for two years. They are also not allowed to bring in a third-party to test the quality of their product.

“It’s heartbreaking. Being able to say, ‘Yes, you can get it,’ but reading over the whole law there is still some things we have to jump over,” said Cristina Ollervidez, 31, who lives near the Texas-Mexico border and is three hours from the closest participating doctor. Her 7-year-old daughter, Lailah, has a type of epilepsy called Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and is in a wheelchair.

“Seeing Texas put limitations, I do get that part,” Ollervidez said. “But I don’t think they did their exact research.”

Texas is similar to more than a dozen other states that only allow access to a low-THC cannabis oil. However, Texas has only licensed three dispensaries, none of which are in the western half of the state or in fast growing cities along the border with Mexico.

“If you’re willing to take a long-term view and you’re willing to suffer a few scars along the way, that success will come,” Morris Denton, who runs the Compassionate Cultivation dispensary near Austin, said. “The lessons themselves represent a barrier to entry for others who may come in. But I think it’s hard to pinpoint how, where and when to start a legal medical cannabis industry.”

Republican Stephanie Klick, the driver behind the Texas law, strongly opposes the social use of drugs and did not support expanding her law this spring. She said it took her 18 months to gather enough votes in the Legislature and convince opponents that patients weren’t going to abuse the cannabis oil.

“There was one sheriff that thought these kids were going to be juvenile delinquents and end up in his jail. And these are really sick kids,” Klick said, noting that lawmakers will consider expansion only after they’ve seen the results of the current framework.

According to Kristen Hanson, a program director for NCSL, it is unusual Texas requires that a doctor “prescribes” the cannabis oil instead of using the word “referral” like most states.

Dr. Paul Van Ness, a neurologist at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, said he supports the restrictive nature of the Texas program, though he admits the downside is limited access.

“They didn’t belong in jail, but that’s what happens in Texas,” Van Ness said. “So if they can do it legally, that’s a lot safer.”